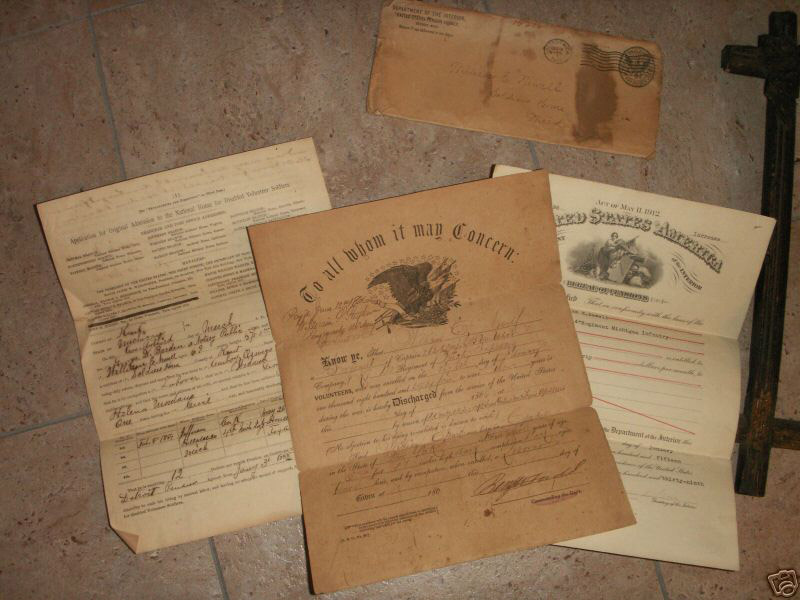

This very unusual file was found among the thousands and thousands of Civil War records being kept in the National Archives in Washington D. C., most of which may eventually be digitized. I found it to be such an interesting case that I asked one of my researching friends, Jonathan Diess, to go to there and copy the files for me so that I could post them here on this site. Jonathan is very efficient and experienced, so I had the case file in hand shortly after submitting my request to him.

On October 4, 1887, Attorney Milton Dashiell, of the International Law Association, in Cincinatti, Ohio, wrote a letter to the Commissioner of Pensions in Washington D. C., on behalf of his client, Mrs. Elizabeth Davis. The letter was written with regard to the two claims that she had sent to the government, “one for pension for being wounded, and the other for services”. It is unknown at this time when she actually submitted her original claim to the United States War Department, but the Adjutant General’s Office, and according to the dates stamped on some of the documents, it was being processed by the Second Auditor’s office on March 7, 1888.

Both of the claims that were made by Elizabeth Davis show a connection during the Civil War between her and the regiment of the Fourth Michigan Infantry. And that, of course, is why the claims have been shared here. According to the letter written by attorney Dashiell…

“Elizabeth Davis, widow of Lorenzo Davis, being duly sworn, says that on, or about the month of September, A. D. 1861, she had entered the 4th Michigan Regiment under First Commissary Sargeant as laundress, at Munson’s Hill, Virginia, at sixteen dollars per month, payable every two months.”

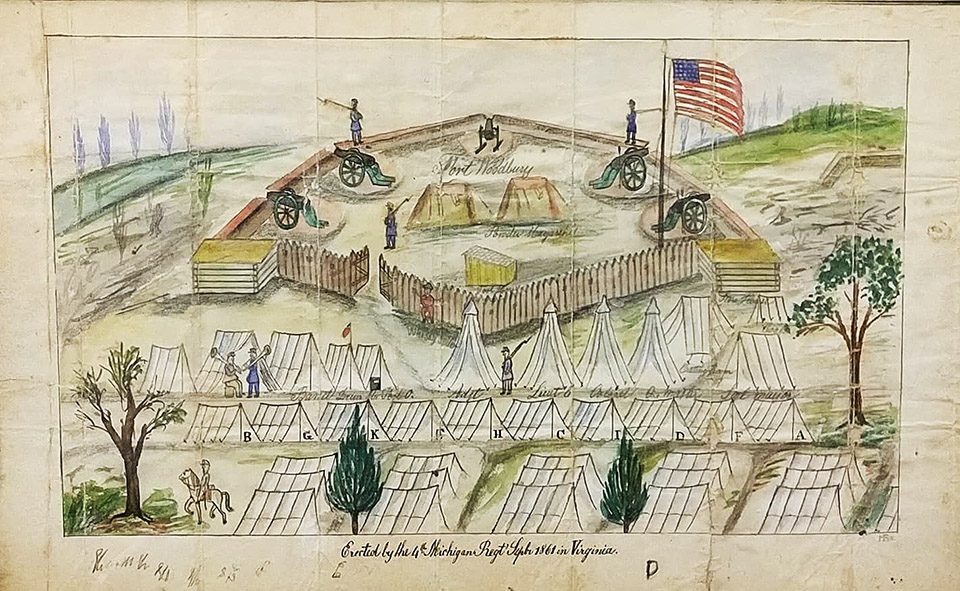

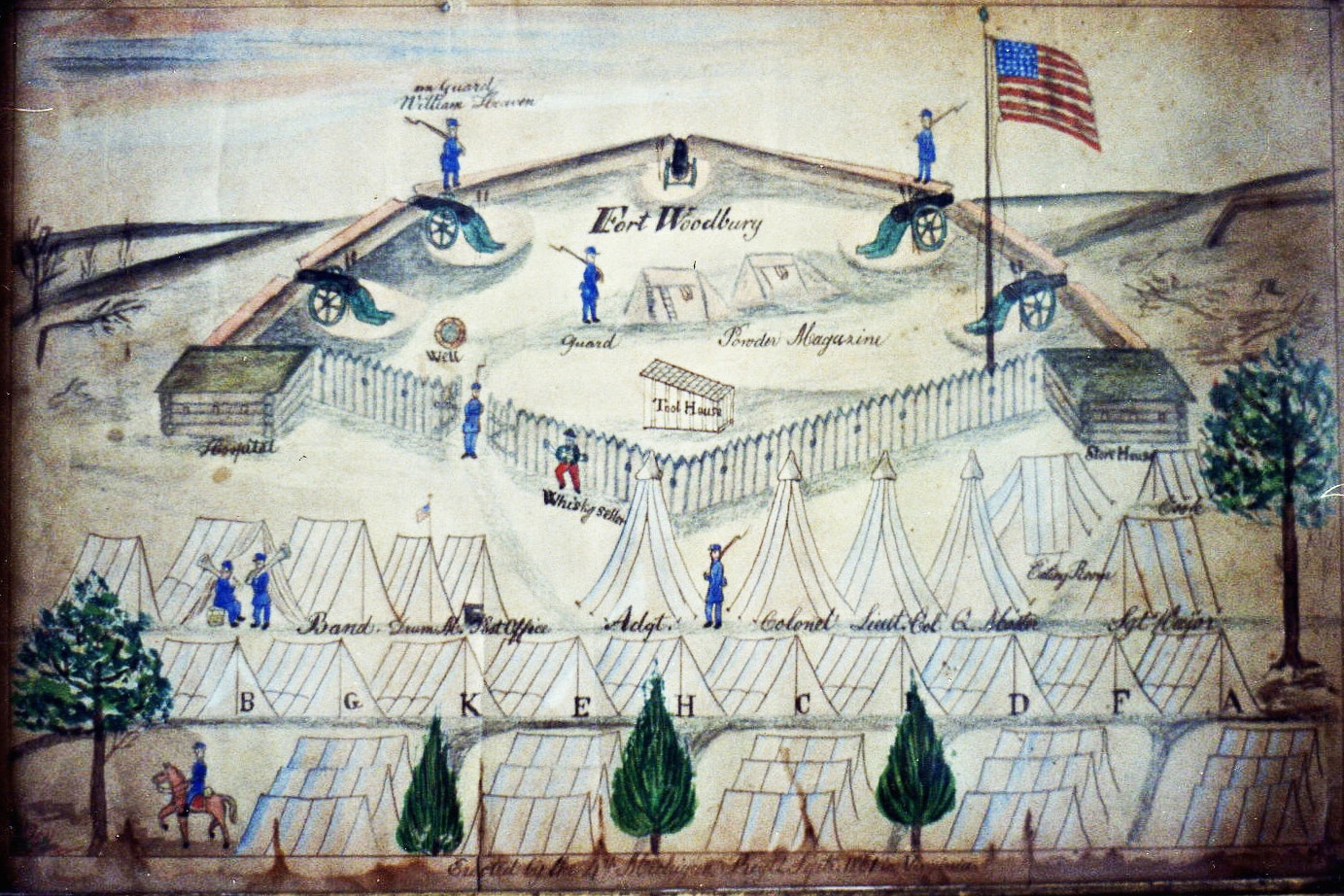

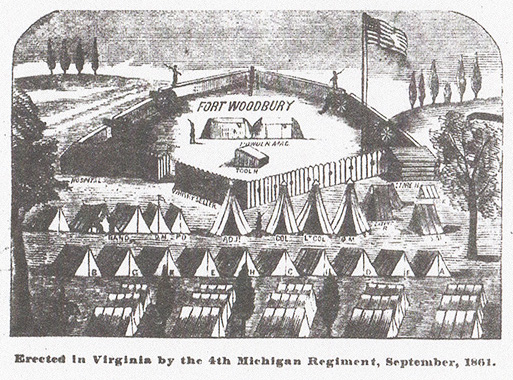

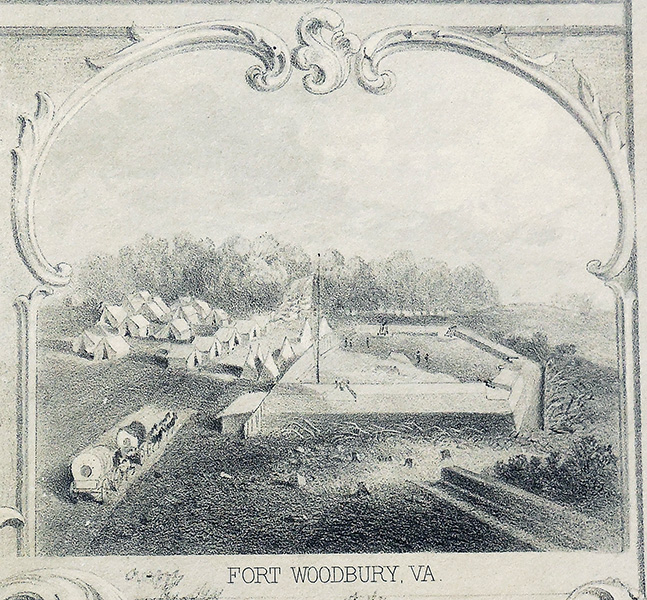

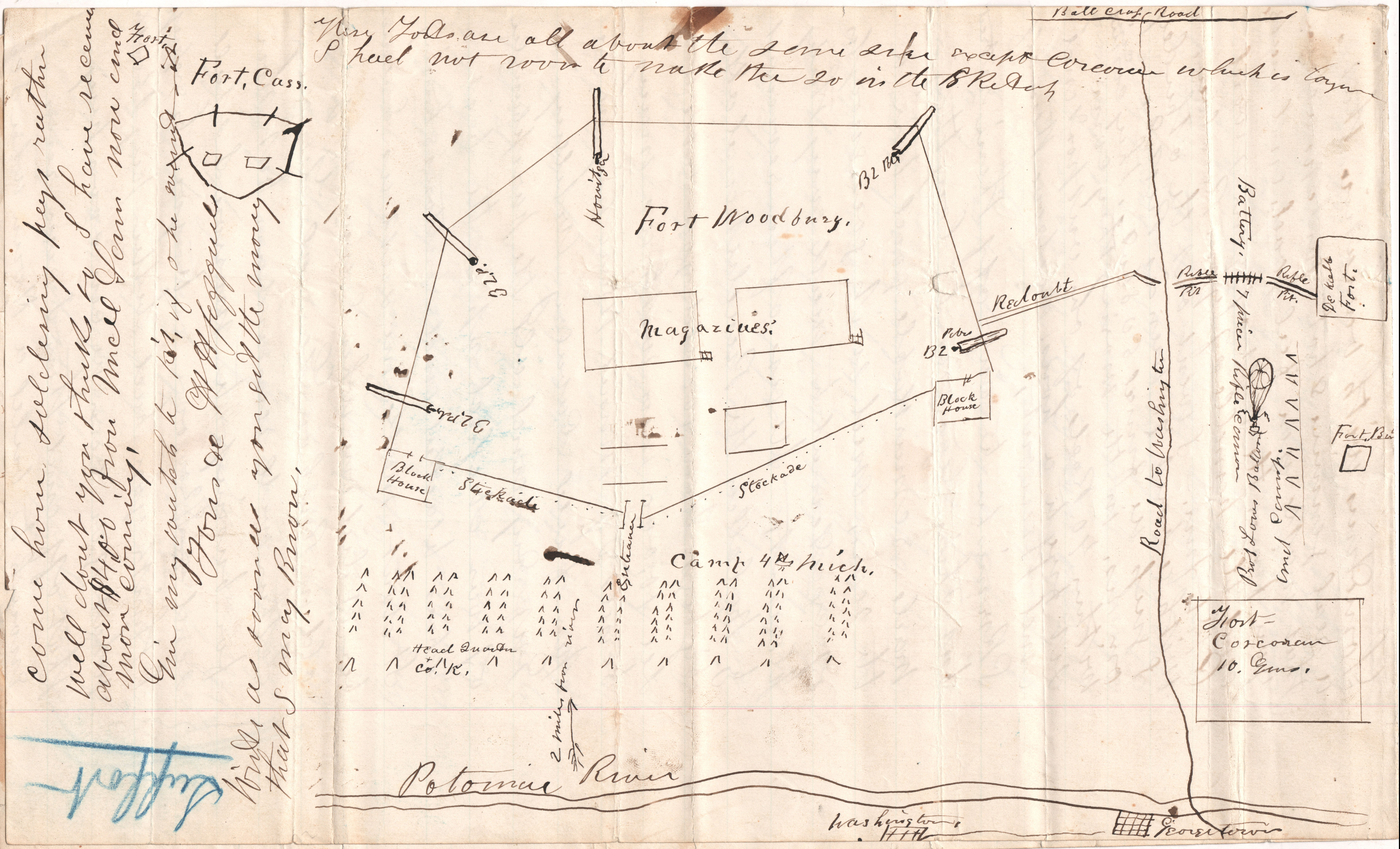

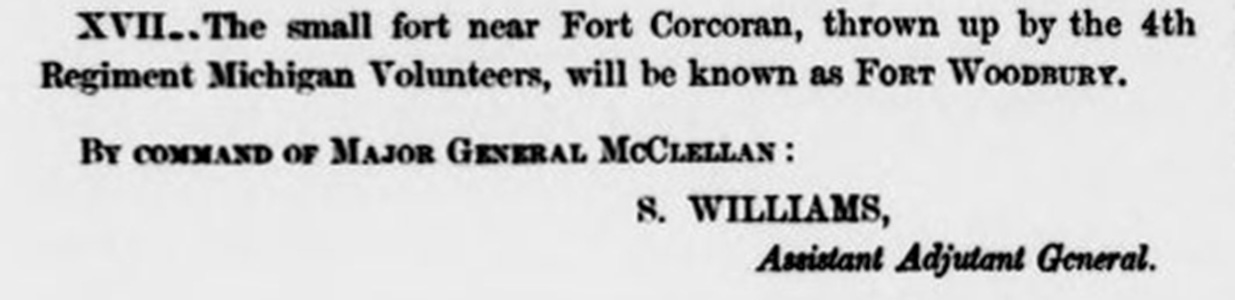

During the late summer and early fall of 1861, the Fourth Michigan Infantry were encamped at Fort Woodbury which was only 2 1/2 miles from Munson’s Hill, Virginia, so this portion of her statement in the claim appears to be valid. Her employer, the “First Commissary Sergeant” of the Fourth Michigan Infantry, may have been 24-year-old Sergeant Edwin S. Baldwin, who enlisted in the regiment and was given that position on June 20, 1861. However, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant of Company D on September 1, 1861, so it is not definitive that he was actually Elizabeth’s employer during the event. Another soldier that Mrs. Davis may have been working for during that time could have been Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant, Selah Reeve Van Duzer. Yet, that seems unlikely as he was transferred to the Second Michigan Infantry on September 1, 1861. So, at this point in time, it is uncertain which individual of the Fourth Michigan Infantry that she could have been working for as a laundress in the fall of 1861. Further research is obviously required for that.

The letter continues by stating;

“that she was wounded about the middle of November of the same year (1861), between Munson’s Hill and Miner’s [Hill], by being shot by Mounted Rifle Rangers of New York, in the back, the ball penetrating the flesh against the vertebrae, passing between the shoulder blade and the ribs around the left side, breaking two of claimant’s ribs of her left side.”

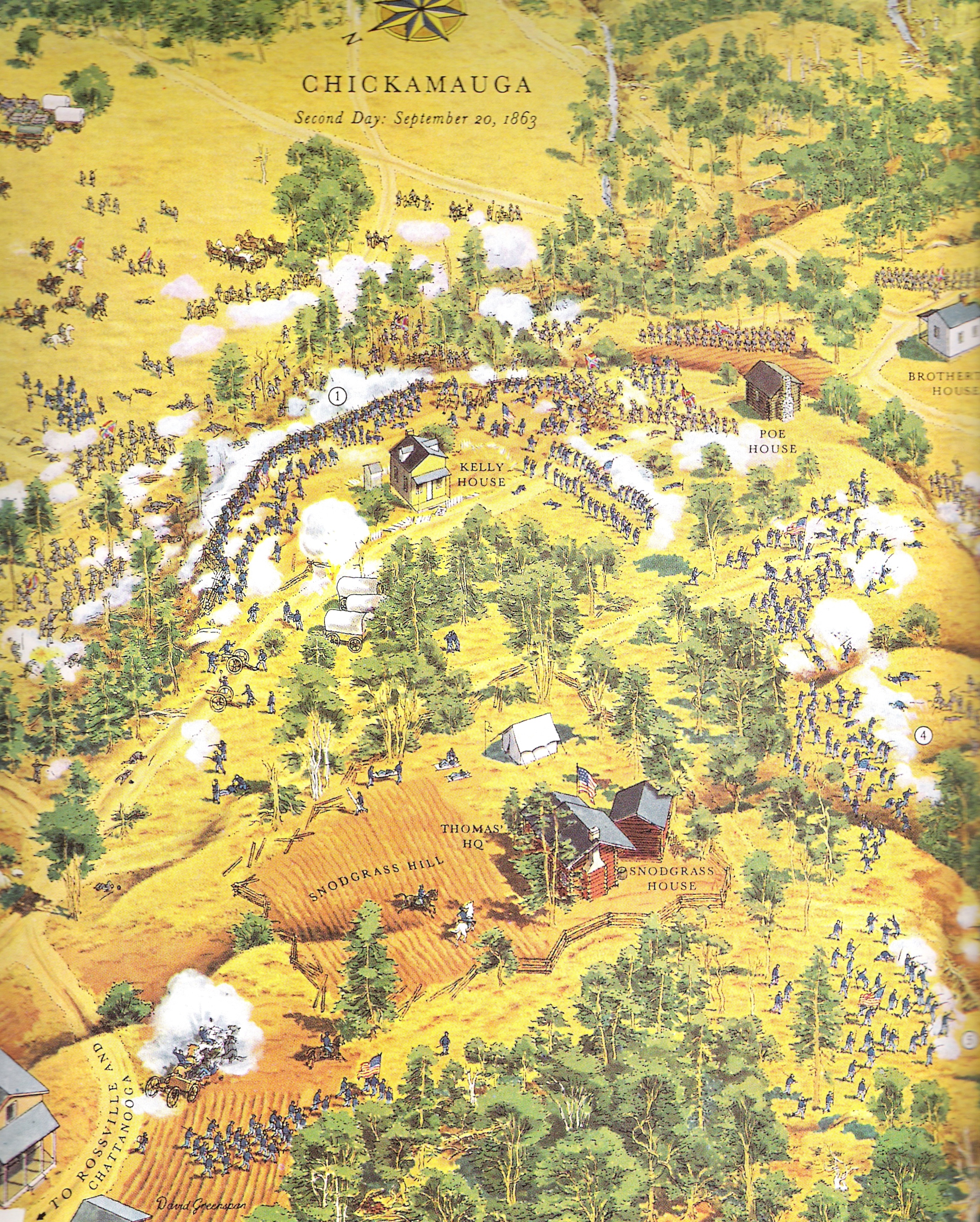

The Fourth Michigan Infantry had left Fort Woodbury (Upper right on map) by late September of 1861, and moved to their new campground about five miles away at Minor’s Hill (upper left on map) by early October of 1861. So, the location of her shooting with relation to the camp of the Fourth Michigan Infantry, and her employer, the Commissary Sergeant seems pretty plausible. The various details that Elizabeth Davis provided strongly suggest that she had a legitimate claim, worthy of further investigation by the United States War Department, as stressed by attorney Dashiell.

As for those who were accountable for the shooting, a preliminary investigation found that there were two New York Cavalry units that may have been responsible, both having been posted in the area during the time of the shooting:

Colonel Andrew T. McReynolds, and the 1400 troopers of the First Regiment “Lincoln Cavalry” of New York had left the state by detachments between July 21, 1861, and September 10, 1861, and were attached to the Defenses of Washington and Alexandria, Virginia, from October 4, 1861, until March of 1862. So, it is quite possible that the individual/s of the “Mounted Rifled Rangers of New York” that shot Miss Davis served in this regiment. These men were stationed near Ball’s Cross Roads (located in the center of the map shown above) as of October 10, 1861.

A second possibility is that the shooter/ shooters served with the Second New York Volunteer Cavalry, unofficially known as the “Harris Light Cavalry”. This regiment had been on duty in the Defenses of Washington as part of McDowell’s Division (Army of the Potomac) as of October of 1861 until March of 1862.

Both of these New York Cavalry units were on duty as part of the Defenses of Washington, and in the same area of Virginia, during Elizabeth’s shooting during November of 1861.

The specifics in her application regarding the identification of those responsible for her shooting, and the medical details of her gunshot wound, add some further legitimacy to her claim.

In September of 1888, an additional document from the War Department, Adjutant General’s Office which was returned to the Second Auditor’s Office, states that “No record of service of Elizabeth Davis in 4th regt. Mich. Vols.” was found. As Elizabeth Davis stated that she had been entered the Fourth Michigan Infantry under First Commissary Sergeant as a laundress, she was very likely employed under a “personal contract” and employed by that specific officer (the First Commissary Sergeant), rather than serving as a laundress and a member of the regiment of the Fourth Michigan Infantry. The fact that her name was not found on the regimental muster rolls would certainly seem to prove that. Elizabeth may simply have assumed that she was working as a hired civilian member of the regiment.

She stated that she was in the “Regiment Hospital of Cavalry in Washington City under the care of Dr. Hewitt”. Research indicates that during that time, there was a 26-year-old assistant surgeon in the 50th New York Infantry by the name of Charles N. Hewitt, and his regiment was on duty in the area of Hall’s Hill, Virginia. Hall’s Hill is only three miles from Fort Woodbury, and 2 1/2 miles from the Munson’s Hill area, the location where Elizabeth’s alleged shooting occurred. Charles Hewitt may, or may not be, the surgeon who treated her wounds, but he is certainly a possibility.

Elizabeth, in her claim, provided some details which were unable to be verified, however. Elizabeth stated that a Captain Burch of the 1st Washington D. C. Cavalry assisted Dr. Hewitt in taking her to her home on F Street in Washington D.C. Looking the map below, you’ll find that there actually was an “F Street” in Washington D. C. (running left to right through the middle of the map seen below).

There were government buildings, various businesses, and some residential areas along F Street in Washington D. C. during 1861. This war time image (courtesy of the Library of Congress) shows the United States Patent Office on the right of F Street. In addition, the Central Office of the Sanitary Commission was also located on F Street during the war.

While many of the minute details given by Elizabeth seem to support her claims legitimacy, some of the other details have little or no verification at this time. One of those concerns is that the First D. C. Cavalry, the unit that she claimed “Captain Burch” was serving in when he assisted Dr. Hewitt in taking her home to recuperate from her treatment, was not even mustered into military service until late 1863. Neither is there a record of a Captain Burch serving in that regiment. Additionally, there was no explanation given by Elizabeth as to why the bullet wasn’t removed until 1882, 21 years after her shooting occurred. No records have yet to be found for a “Regimental Hospital of Cavalry of Washington D. C., which is where she said that she had been initially treated for her wound by Dr. Hewitt. Further research is warranted as to which hospital it was that she may have intended to state in her claim.

In the very least, Elizabeth’s claim is a very interesting one of a possibly unique historical event. It is certainly compelling, and I believe it to be something that did indeed happen, though I can’t say that definitively. I know of no other accounts where a Civil War laundress claimed to have been shot during the Civil War, and unfortunately, we do not have the complete story as to why the shooting occurred. For now, we only have what is found within this historic file. I hope that one day additional information will be brought to light from within the National Archives collection, something that may answer the questions that we’re left with until then.